There were seismic shifts in energy, major medical advances, animal comebacks, four-day week trials, a night train revival, plus plenty more good news

The 2022 good news roundup

Two things happened this year that may have changed the energy paradigm forever. The first was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the West’s subsequent dash to wean itself off Russian gas while ramping up renewables.

Putin’s war was “a historic turning point towards a cleaner future,” said the International Energy Agency, which for the first time predicted global demand for fossil fuels would peak in the mid-2030s due to the conflict.

Even without the war, the economic and moral case for fossil fuels looked ever weaker in 2022, with Lloyds and HSBC among the banks pledging to stop funding new oil and gas fields. By contrast, investment in renewables surged.

While the smart money moved towards wind and solar, in a Californian laboratory scientists gave the world a glimpse of the energy of the future. US physicists cracked one of nuclear fusion’s biggest mysteries, bringing the prospect of near-limitless, low-carbon energy a step closer.

Image: Denys Nevozhai

The climate crisis came into sharper focus in 2022, with more alarming reports and extreme weather. As it stands, the world is on course for 2.5C of warming by 2100, according to the United Nations. This is higher than the “upper safe limit” of 2C, meaning more radical action is needed.

Encouragingly, there were signs of progress. The US (the world’s second largest emitter after China) approved legislation to turbocharge its decarbonisation programme. Analysis suggests that it could slash US emissions by 44 per cent by 2030. The EU also set a target of reducing emissions: by 55 per cent this decade.

Climate litigation emerged as an effective tool for bringing about positive action in 2022, with high-profile wins, including a Filipino ruling that stated big polluters were “morally and legally” liable for climate damage.

“Climate litigation cases have played an important role in the movement towards the phaseout of fossil fuels,” commented the London School of Economics, which said climate-related lawsuits have doubled since 2016.

Image: Luke Thornton

For decades, poorer countries have implored richer nations to compensate them for the damage caused by climate change. For decades their calls have gone unanswered. Until now.

In the Egyptian desert in November, delegates at the COP27 climate summit agreed to set up a ‘loss and damage’ fund to help developing nations deal with a crisis that they’ve barely contributed to.

Exact details have yet to be thrashed out, but the pledge was considered a win from a summit that otherwise underwhelmed. It followed earlier commitments from Denmark and Scotland to compensate poor countries for climate damage.

Image: Damian Patkowski

The magnitude of the climate crisis leaves many people wondering how much difference they can really make. But research published this year suggested citizens have direct influence over 25-27 per cent of the emissions savings needed to avoid climate chaos.

The study was led by academics at Leeds University, which suggested six lifestyle changes that could help slash emissions. None of this absolves governments and corporations of their responsibilities, but it does provide a welcome sense of agency.

Image: Adolfo Felix

In the ultimate mic drop gesture of corporate responsibility, the owner of multi-billion dollar clothing firm Patagonia gave the company away to help fight climate change.

“Earth is now our only shareholder,” announced the company’s CEO Yvon Chouinard (pictured), who said that every dollar of profit that’s not reinvested back into Patagonia will go towards protecting nature and biodiversity.

Patagonia’s move is part of a broader trend for businesses to expand their remit beyond simply making money. Other firms have given nature ‘a seat on the board’, tied bonuses to sustainability targets, and used algorithms to clean up supply chains. Expect the trend to accelerate in 2023.

Image: Patagonia

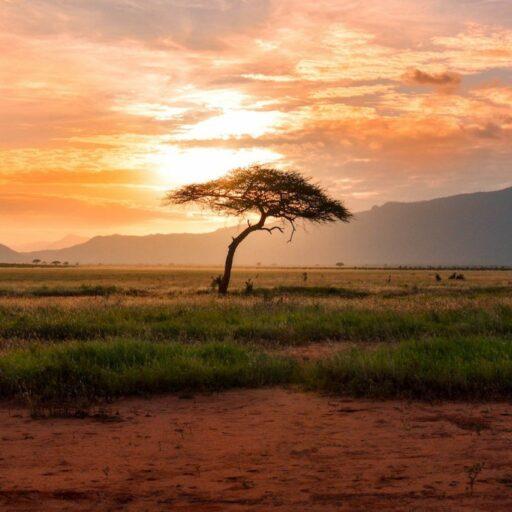

The list of endangered species continued to grow at an alarming rate, but some creatures bounced back from the brink in 2022, proving that extinction is not inevitable.

Beavers, bison and pelicans were among the species identified as having bucked the trend by the Wildlife Comeback Report, published in September. Most are the subject of reintroduction programmes, including the bison, which is roaming England again for the first time in thousands of years.

Other notable success stories include the rhino’s return to Mozambique, the reported resurgence of fin whales, and the tiger clawing its way back from the abyss.

There’s much work to be done, but these conservation wins brought hope. So did December’s COP15 global biodiversity deal, which committed the world to halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030. A deal on protecting sharks was another notable victory.

Image: Aditya Pal

In March, wildlife-rich Panama became the latest country to introduce a rights of nature law, joining the likes of Ecuador, Mexico and New Zealand.

Passing such a law is one thing, enforcing it is another. In Ecuador, some controversial extraction projects have continued in ecologically sensitive regardless, although the law has successfully prevented others from proceeding.

Image: Dimitry

The year drew to a close with the news that nations have struck a deal to protect a third of the planet for nature by 2030.

It wasn’t the only sign of progress. In California, a swathe of redwood forest was handed back to the descendants of Native American tribes; Ecuador ruled that indigenous communities must be given more autonomy over their territory; Europe removed a record number of dams, returning hundreds of rivers to their original free-flowing state; and England got its first wetland ‘super-reserve’.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, the incoming president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, pledged to halt deforestation and revive the Amazon Fund, which enables rich countries to finance conservation in the Brazilian rainforest.

Image: Goldman Environmental Prize

There’s cautious optimism that the civil war in Ethiopia could finally be over, after the warring sides agreed to permanently end hostilities in November.

The two-year conflict between the government and Tigray People’s Liberation Front has displaced millions and caused misery for many more.

Representatives of both sides signed up to a disarmament plan, and agreed to restore crucial services, including aid supplies.

Image: Taylor Turtle

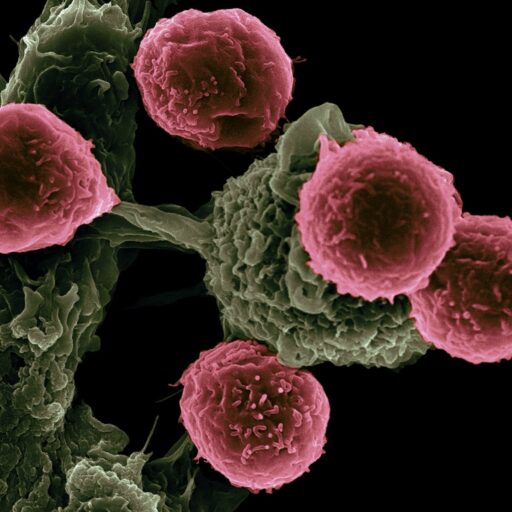

New fronts in the fight against cancer opened up this year, with scientists developing better tools for detecting and treating the disease.

Tests were developed that appear to be able to diagnose cervical cancer, prostate cancer and other forms of the disease using blood and urine samples, and other non-invasive checks. Research is ongoing, but it looks promising.

Experimental treatments also provided some good news. In December, a teenager who had been diagnosed with “incurable” leukaemia was cured, thanks to what scientists say is the most sophisticated cell engineering to date.

Similarly, a woman who didn’t think she would make it to last Christmas has been celebrating a new lease of life, having had a remarkable response to an experimental bowel cancer drug.

Meanwhile, in the biggest study of its kind, researchers harnessed the power of whole genome sequencing to unearth a “treasure trove” of clues about the causes of cancer – findings that could improve patient diagnosis and outcomes.

Image: National Cancer Institute

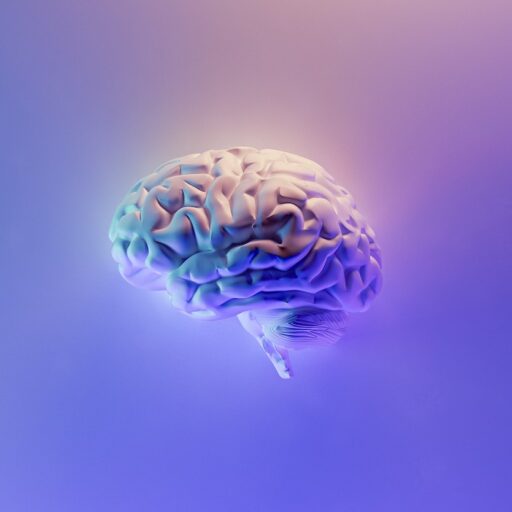

The hitherto futile search for an Alzheimer’s cure took a major step forward in November, after a new drug was found to slow the disease.

Lecanemab works by clearing the amyloid protein that builds up in the brains of people who have Alzheimer’s. In a clinical trial, it was found to slow cognitive decline, a development described as “a major step forward for dementia research.”

Separately, an international study of Alzheimer’s disease pinpointed 75 genes associated with the disease, including 42 that were not previously linked. Identifying specific risk genes and the part they play in brain cell death could pave the way to new therapies, researchers said.

Another study identified seven habits that people can adopt to cut the risk of developing dementia: exercising regularly; eating healthily; not smoking; maintaining a healthy weight; keeping blood pressure in check; having healthy cholesterol levels; and maintaining healthy blood sugar levels.

Image: Milad Fakurian

Among the other notable medical achievements this year was the development of a bioengineered cornea, which restored the sight of 20 people in a clinical trial. The breakthrough could help the estimated 12.7 million people globally whose corneas are damaged or diseased.

Treatments also improved for rare blood disorders and malaria, with researchers declaring a new malaria vaccine the “best yet”. The charity Malaria No More said that infant malaria deaths could end “in our lifetimes” thanks to the drug.

Meanwhile, some of the largest trials to date involving psychedelics suggested hallucinogenics could provide an effective treatment for addiction, depression and other mental health conditions when combined with talking therapy.

Image: Mathew Schwartz

It might not seem like it sometimes – particularly in 2022, year of the so-called ‘permacrisis’ – but the world has mostly become a better place to live in during the last 11 years.

That’s according to the latest Social Progress Index, published last month. Each year, it assesses life in 169 countries, giving annual scores for nations and the world as a whole. Despite the good news, the index showed progress was uneven and slowing.

The UK, for instance, was identified as one of four countries in a “social progress recession”. The others were Syria, Venezuela and Libya.

Mercifully, a separate study found that despite attempts by some to divide the UK, a tolerant centre ground prevails. It reported a “surprising and reassuring sense” of unity among Britons, even on supposedly divisive issues such as race and identity. A report by the National Centre for Social Research reached a similar conclusion.

Image: Adli Wahid

The year began with an encouraging report by Human Rights Watch, which suggested autocrats were losing their grip on power.

Putin’s subsequent invasion of Ukraine may have dispelled that, but there was ample evidence to suggest it was true elsewhere. Not least in Brazil, which voted out president Jair Bolsonaro, a hardliner whose policies accelerated deforestation in the Amazon.

Another significant election took place in Australia, which ousted Scott Morrison, a prime minister who mocked the seriousness of the climate crisis.

And in the US midterms, champions of democracy were relieved to note that candidates perpetuating the ‘stolen election’ conspiracy performed poorly.

Image: Dan Freeman

A report in June confirmed what our readers have been telling us for years: that the mainstream news is overwhelming people with negative stories, and forcing them to switch off.

Positive News was invited to appear on BBC World News to discuss the findings, and to highlight the importance of balancing negative stories with stories about solutions.

Our team was also emboldened by the release of another report in November, which suggested solutions journalism boosts support for climate action. That might explain the enduring popularity of this story: what can I do about climate change? 14 ways to take positive action.

Our audience continued to grow during the year, as did our community of supporters who are helping us to break the bad news bias. Good news indeed.

Image: Positive News

While the US supreme court withdrew its support for women’s reproductive rights, Sierra Leone and Malta were among those that went the other way.

Scotland, meanwhile, became the first country to guarantee the right to a free period, England launched its Women’s Health Strategy to close the gender health gap, and the English health service announced flexible working for women going through the menopause. In fact, it was a year when it felt like the taboo around the menopause was finally breaking.

Women also scored notable victories in sport. The Euro 2022 final between England and Germany netted the largest TV audience for a women’s match in UK history. And despite taking place in a country where women’s rights are limited, the men’s World Cup celebrated a welcome milestone: for the first time, a female ref officiated a game.

Image: El Loko Foto

This year saw more progress in tackling discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community, although there is still much work to be done.

Greece and Israel became the latest countries to ban conversion therapy, Slovenia ruled that its ban on same-sex marriages was unconstitutional, uber-strict Singapore pledged to decriminalise homosexuality, and Tokyo formally recognised same-sex partnerships (despite homosexuality being illegal in Japan).

And in the US, Congress approved legislation guaranteeing federal recognition of gay and interracial marriage. The bill was born out of concern that the supreme court could reverse its support for same-sex marriage as it did with abortion rights.

Image: Stavrialena Gontzou

A ban on plastic packaging for fruit and vegetables came into force in France on New Year’s Day – the opening salvo in a year that saw efforts to curb plastic pollution ramp up.

The most significant development came in March, when 175 nations agreed on a “historic” resolution to end plastic pollution. The EU subsequently unveiled its own plan to cut plastic, while India outlawed some of the most commonly littered plastic items.

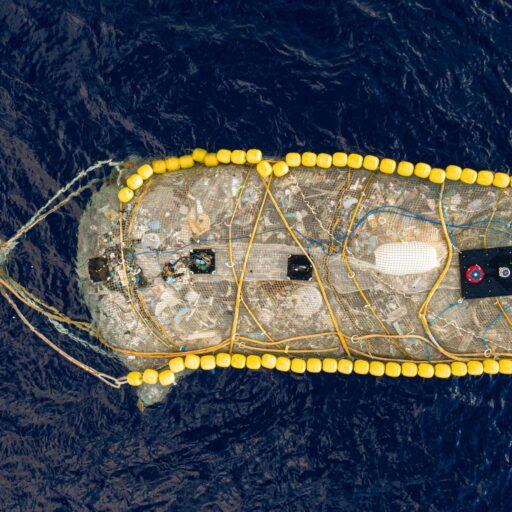

Too late for all the plastic that’s already at sea, which is where Ocean Cleanup comes in. The social enterprise is tackling the Great Pacific garbage patch using booms that skim the waves for plastic. This year, it said that it had removed 100,000kg of plastic.

In further good news, scientists found a way of destroying toxic ‘forever chemicals’, and discovered that worm spit can help break down plastic.

Image: The Ocean Cleanup

This year witnessed some creative ideas to kickstart culture following the pandemic, not least Ireland’s basic income for artists. The €325 (£270)-a-week stipend launched to support thousands of struggling creatives, who will receive the payments for three years.

Meanwhile, Germany became the latest country to give citizens the gift of culture. Those turning 18 next year will be entitled to a €200 (£175) ‘KulturPass’, which can be put towards gig and theatre tickets. France, Spain and Italy have launched similar schemes.

Image: Matheus Ferrero

Proponents of a shorter working week have long argued that it would improve life satisfaction without impacting productivity. This year, more firms were swayed by the idea.

In September, a groundbreaking four-day week pilot got the thumbs up from almost nine out of 10 firms taking part, with 86 per cent saying they plan to keep the new model.

Even companies not taking part appeared to be embracing shorter working weeks. According to a survey by the University of Reading in England, 65 per cent of UK businesses now offer truncated working weeks, compared to 50 per cent in 2019.

Meanwhile, in Belgium, workers were given the right to request a four-day week.

Image: Alistair Macrobert

While drugs policies are typically shaped by public opinion instead of evidence, this year brought more signs that a new approach is emerging.

In a move unthinkable a decade ago, the UK government granted a licence for a service that anonymously tests people’s drugs for strength and purity – information that could save lives amid record drug deaths.

And in the US, President Biden pardoned thousands of people convicted of “simple marijuana possession”. The pardons applied only to federal offenders, impacting around 6,500 individuals, according to local media. Biden urged state governors to follow his lead.

Image: Unsplash

Efforts to slow down fast fashion gathered pace this year with big name retailers launching rental and repair services for clothes. John Lewis and Selfidges led the charge in the UK. The latter said it wanted 45 per cent of all its sales to be driven by circular products by 2030.

The UK also got its first ‘fixing factories’, where volunteers repair faulty items – be they electronics of push bikes – on a pay-what-you-can-afford basis. Both are in London, but the organisations behind them want to open one on every high street. Amsterdam has similar ideas.

Image: Restart Project/Mark Phillips

The race to decarbonise air travel accelerated this year, but don’t pack your suitcases just yet. Air Nostrum, a Spanish carrier, placed an order for 10 low-carbon airships that could replace planes on some short-haul routes. Departure dates have yet to be confirmed.

In Sweden, an aviation startup unveiled a 30-seater electric plane and said it had already landed orders from major airlines. Meanwhile, in the UK, a British-built aircraft became the latest battery-powered plane to complete test flights.

Aviation was the fastest growing source of emissions before the pandemic. Recognising the scale of the problem this year, nations agreed to a long-term plan to cut aviation emissions, albeit a decidedly woolly one. France went further by banning domestic flights where there’s a train alternative that takes less than 2.5 hours.

Image: Heart Aerospace

Electric trains produce up to nine times less carbon dioxide than planes. But what about on routes that can’t be electrified? Germany may have the answer.

This year, it launched the world’s first 100 per cent hydrogen-powered trains, which have been put to work on a line near the German city of Hamburg, where they whirr along emitting only water.

While hydrogen-powered trains produce no direct carbon emissions, the fuel is only ever as green as the energy used to create it.

Image: Alstom

Pushed towards extinction by budget airlines, Europe’s forgotten sleeper trains staged a comeback in 2022 amid rising demand for green travel.

New nighttime services included Paris to Vienna and Hamburg to Stockholm. “A better experience [compared to flying] and climate change are driving mainstream travellers to look at train travel,” rail industry expert Mark Smith, told Positive News.

This year also saw the launch of new low-cost rail services, including Iryo in Spain. Meanwhile, the UK’s own budget operator, Lumo, succeeded in tempting more passengers out of the skies on Britain’s busiest domestic route.

Image: William Daigneault

Main image: Spencer Wilson

Get a weekly fix of good news delivered to your inbox every Saturday, by signing up to the Positive News email newsletter. And if you’d like to back our solutions-focused journalism and help us to break the bad news bias in the media, please consider making a monthly contribution as a Positive News supporter.

This article was updated on 24 January to remove erroneous figures concerning the number of marijuana convictions quashed in the US.