Guatemalan parents have an enviable childcare situation and ‘stringers’ have the best job on earth – behind the scenes on our Developing Mental Wealth series

We’re halfway through our series looking at the people and projects really changing lives through boosting people’s mental health in all four corners of the globe. From Yemen to Liberia and Guatemala, what have we learned so far? Series editor Daisy Greenwell reports.

1. ‘Stringers’ have one of the best jobs in the world

You may not have heard of the term ‘stringer’, but you will have read their work. Stringers are freelance journalists who report on the ground in all sorts of countries for news organisations, so named for the string that once measured their column inches (and determined their pay). So far during this series we’ve commissioned reporters in six countries, sending them into the heart of some of the most impactful mental health projects around the world. Often, I’ve wished that I could be there rather than at my desk in England, talking face-to-face with the visionary founders and the people whose lives they are changing. There aren’t many jobs that allow such an opportunity to get up close, asking as many questions as you like, of the people who are really changing things.

2. Reporting in the global south is a lot more complicated than in the UK

Behind every article we publish is a whole lot of sweat, thought and logistical jiggery pokery from a team of people, from editor to journalist, photographer and interviewees. Ensuring everyone is in the same place at the same time can be a logistical challenge. Even more so, it turns out, when it’s taking place in a country that’s 5,000 miles away, both geographically and culturally.

For our article published earlier this month on the Indigenous women’s circles that are empowering Guatemalan women after decades of marginalisation, we commissioned Sandra Cuffe, a journalist in Guatemala, to visit the project. She immediately came up against an unusually physical barrier to executing her commission.

Cuffe explains: “Indigenous leaders led months of protests for democracy, including weeks-long highway blockades, in response to prosecutors’ efforts to subvert the outcome of elections. Reporting in a country like Guatemala can be tricky, because between political crises and the poor state of the country’s highway infrastructure, there is no guarantee travel is possible.”

We encountered a different, but equally difficult problem in Yemen, when trying to photograph the members of Best Team, a free sports group that has spread across the country, helping people stay fit and healthy during an ongoing civil war. On the eve of the photographer’s visit to al-Thawra Park in the Yemeni capital Sanaa, where one of the groups meets before dawn prayers, the government announced a ban on groups of people from gathering outside. His photoshoot was scuppered for the foreseeable future.

In each case, we had no choice but to be flexible, adjust our plans, and plough on regardless. Note to self – an article that would take a few weeks to come to fruition in the UK may take twice that when working in countries such as these.

Yemeni men exercise together in the capital city Sanaa’s al-Thawra Park, as part of the free Swedish exercise club 'Best Team' that has swept across the country. Image: Reuters

3. Guatemalan parents have an enviable childcare situation

When photographer James Rodrigues filed his shots of the Indigenous women’s circles project in Guatemala, we were interested to spot lots of women who were carrying on their backs babies that weren’t their own. It seems that parenting in Guatemala is different to the UK – it’s shared out more equally among the community. It chimed with a new University of Cambridge study of the Indigenous Mbendjele BaYaka in the Republic of Congo, which had caught my eye. The researchers found that in this community, more than half of a baby’s cries are attended to by the mother’s support network rather than her. Would a British mother who is home alone all day with her baby, agree with the authors of the study, who concluded that there is a ‘mismatch’ between the conditions in which humans evolved to care for babies, and the situation many parents find themselves in today? A straw poll of my friends would suggest 100% yes.

Elsa Cortez, 26, weaves a belt while carrying her 1-year-old niece in Guatemala. The women's circles run by Indigenous women locally have transformed her life. Image: James Rodriguez

4. Once again, Nordic countries lead the way

What is it about the Nordic countries and their ability to top virtually every ranking of human development, from public healthcare to education and happiness? Even those experiencing psychosis, one of the most feared symptoms of mental illness, fare better in Finland. Just 15% of people diagnosed with schizophrenia are employed in the UK. In Finland, 86% of patients with severe mental health conditions return to work and education. How? Back in the 1980s when Finland had one of Europe’s highest rates of psychosis, psychiatrists developed a model of care that transformed the outcomes of those in crisis. Now the UK is trialling it, with a five-year study of the ‘open dialogue’ approach at NHS mental health clinics in Dorset, Kent and London. The results are due in April 2024, and the psychiatrists we spoke to believe they could revolutionise treatment of mental illness in Britain, and beyond.

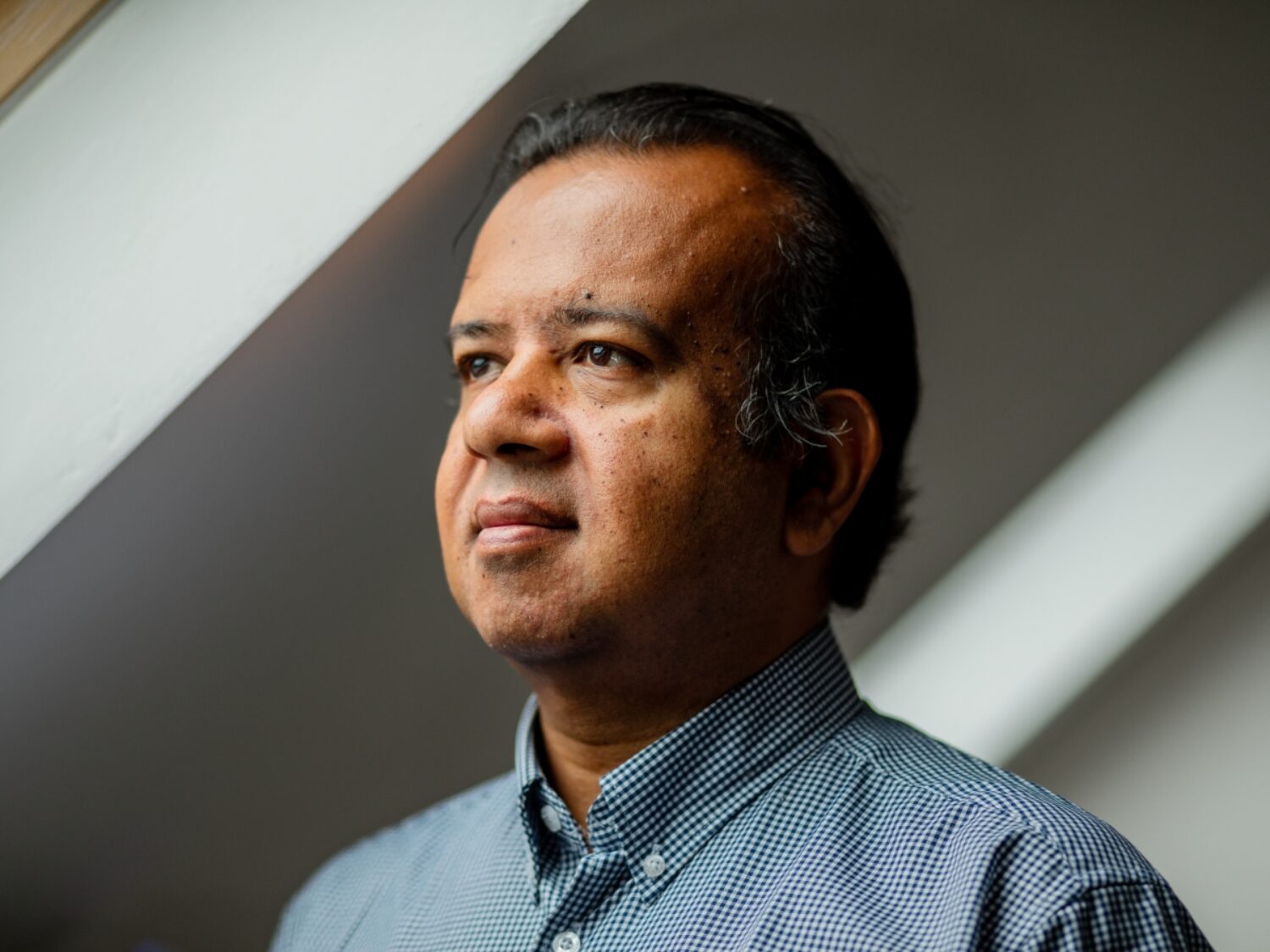

Dr Russell Razzaque, the east London psychiatrist who has been key in bringing the Finnish approach to psychosis, known as 'open dialogue', to the UK. Image: Sam Bush

5. Many of the most exciting grassroots mental health projects are happening in Africa

We are scouring the planet looking for great community-led mental health projects, and time and again, they seem to be taking root in Africa. From the Friendship Benches of Zimbabwe, to the project giving CBT and cash transfers to former child soldiers in Liberia, and the Kenyan NGO aiming to end FGM through intergenerational healing, Africa is often leading the way when it comes to thinking on mental health.

While we want to ensure a good geographical spread in the series, my main priority as editor has to be the stories themselves. Stories that show the most creative, interesting and potentially scalable ways that communities are finding to ease the mental health stressors in their lives. The number of African stories authentically reflects the most exciting developments in the world of mental health. If you have a project to suggest, email me – I’d love to hear from you.

Main image: FGM survivors on a trauma-informed survivor leadership training course given by the Girl Generation in Kenya: Zeitun Abass Omar, Ralia Roba and Dekha Ahmed. Credit: Khadija Farah

Support solutions in 2024

Our small, dedicated team is passionate about building a better alternative to the negative news media. And there’s never been a greater urgency to our mission.

But to invest in producing all the solutions journalism that the world is longing for, we need funding. And because we work in your interests – not those of a wealthy media mogul or corporate owner – we’re asking readers like you to get behind our team, by making a regular contribution as a Positive News supporter.

Give once from just £1, or join 1,400+ others who contribute an average of £3 or more per month.

Join our community today, and together, we’ll change the news for good.